Land Registration etc. (Scotland) Bill 2

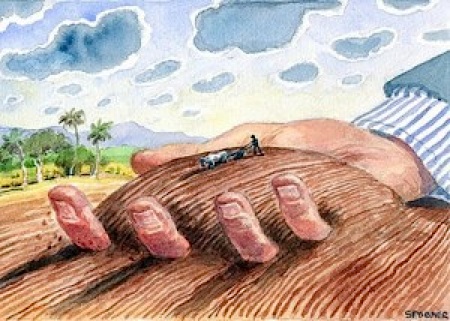

LAND GRABBING

The Land Registration etc. (Scotland) Bill was introduced to Parliament on 1 December with no publicity by the Scottish Government for its fifth piece of legislation of the current session (see previous post). As it stands, it is a missed opportunity to resolve a number of important issues related to landownership in Scotland. In this blog I want to highlight the first of three of these – the legitimacy of a non domino titles and prescriptive possession (Section 42 to 44 of the Bill).

Prescription is a legal device introduced in 1617 which has the effect of exempting a title from legal challenge provided that the land has been occupied “peaceably, openly and without judicial interruption” for at least 10 years (20 years in case of Crown land). As I argue in my book, The Poor Had No Lawyers, this was introduced, along with the Act of Registration to provide legitimacy for land that the nobles had appropriated from the Church in the 16th century. It is telling that the Prescription and Limitation (Scotland) Act 1973 (which governs prescription) states in the preamble that it replaces the Acts of 1469, 1474 and 1617. This is an ancient device and it has served landed interests well.

For example, the Duke of Argyll admitted in the House of Lords in 1815 that the principle of prescription provided the foundation of a “very good deal of the property held by Members”. (1)

And John Rankine, author of the magisterial The Law of Landownership in Scotland went so far as to remark that, “The words of the protection given in the Act of 1617 to this favoured conjunction of title and possession are very full and sweeping, and have been applied …. to many cases which were not properly within the purview of the Act” (2)

It is not, however, within the scope of the Land Registration Bill to deal with the question of prescriptive possession per se (which is covered by Acts of 1973 and 1984). However, the law of land registration is involved since it sets the terms and conditions for prescriptive claims to be accepted and registered (together with all of the accompanying benefits that provides to the applicant).

The particular form of prescription that is covered by the Bill is provision for individuals to lodge a claim of ownership over land they do not own – a non domino titles (literally, “from one who is not the owner”). This is where a deed is recorded for land not owned by the applicant in order to found prescription – in other words to start the clock ticking on the prescriptive period.

The Bill provides a statutory basis for anyone claiming prescriptive title to have it recorded – again this is an area on which the original Land Registration (Scotland) Act of 1979 Act is silent. But should such claims even be entertained in the first place?

The Keeper’s rules for accepting a non domino deeds are outlined in the Keeper’s Registration of Title Practice book here. They have been tightened up in recent years and the Bill tightens matters further by insisting that any claims must relate to land that has been abandoned for the previous seven years and that must have been possessed by the applicant for one year. The applicant must also submit evidence that they have attempted to trace the true owner and must inform the Crown as the ultimate owner of land in Scotland.

But despite such tightening of the rules, the question remains as to whether such first-come, first-served land seizure is desirable in the first place and whether alternative arrangements should be made to deal with land that has no apparent owner. The Policy Memorandum is unconvincing on this point (paras 58-63). Having outlined the advantages of prescription, the Government argues that an alternative approach (not to allow prescriptive claimants) “would not provide the advantages noted above”. I should have thought that was blindingly obvious.

The admission of a non domino deeds causes the law contort itself. Section 42(1) admits openly that such deeds are to be treated as valid despite not being so and limits the grounds on which the Keeper can rule that it is invalid in Section 42(2). Section 1(1A) of the Prescription and Limitation (Scotland) Act 1973 prohibit claims for prescription where a deed is ex facie invalid. One example of such an instance is where a deed plainly reveals that the disponer is not the owner (3)

The Bill overcomes these difficulties by effectively conspiring to accept as valid something which is not, so long as the applicant conceals the fact that it is not. Is this the kind of law the Scottish Parliament is comfortable with? This kind of contorted logic has been developed by landed elites and their legal representatives over centuries. Vast swathes of land have been acquired on the basis of deeds that purport to transfer land that the disponer does not own.

Prescription and a non domino deeds have provided for widespread theft of land over the centuries by the greedy and powerful being able to get their claims in the door first and the innocent bystanders being both ignorant of the attempt and losing their land. Under the current rules, the Keeper is even prohibited from notifying the true owner that a hostile claim has been lodged.

It is time to end this abuse of the law. Instead of the (admittedly stricter) rules set out in the Bill, a far more public process should be adopted. Any claims to “unowned” land should be lodged with the Keeper and then advertised publicly on the Registers of Scotland website for a minimum period of one year. The publicity should include the name of the claimant and their grounds for the claim, the extent of the land being claimed, a report on investigations into its legal history and the conclusions of the research conducted to identify the true owner, and an invitation to lodge rival claims. The view of the Crown should be sought and publicised as it is the ultimate owner of land and could legitimately lay claim.

Only after the expiry of this period should the Keeper have any power to admit an a non domino deed for registration. Any contested claims should be settled by the Lands Tribunal.

Land grabbing of any sort should be ended. In particular, Scotland’s common land should be afforded much greater protection from predatory claims and this will be the subject of my next blog.

(1) Hansard Parliamentary debates 3rd series, vol 192, col. 1815, 19 June 1868.

(2) Rankine The Law of Landownership, 4th Edition, pg. 32.

(3) See Aberdeen College v. Youngson at 14

One thought on “Land Registration etc. (Scotland) Bill 2”

Comments are closed.