Edinburgh Council loses Parliament House

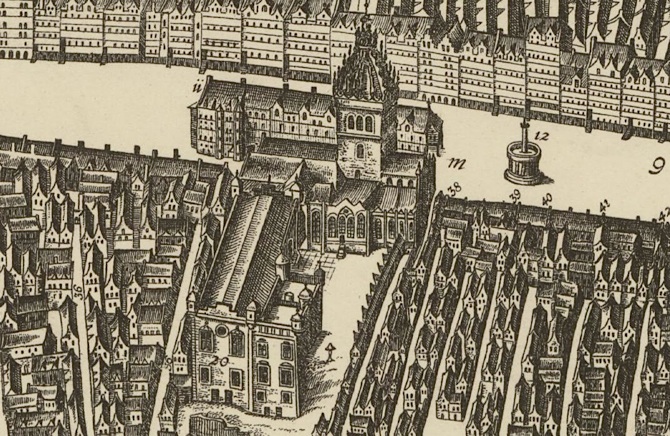

Image: De Wit version of Gordon of Rothiemay’s original 1647 plan showing Parliament House seven years after construction. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland.

Image: De Wit version of Gordon of Rothiemay’s original 1647 plan showing Parliament House seven years after construction. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland.

Regular readers of this blog will be familiar with the subject of common good land. This is land and property in the Burghs of Scotland that is the historic property of the burgh held on behalf of the citizens. (1) This blog has reported on many cases of maladministration of these assets where Councils have been sloppy in their record-keeping and where the interests of the citizen has been poorly served by the Councils that replaced the Town Councils in 1975.

But Scotland’s four ancient cities do not have any real excuse. Unlike Kirkcaldy or Hawick, Glasgow, Edinburgh, Dundee and Aberdeen have enjoyed continuity in having always had a council governing the affairs of the city. So one might expect them to have a good idea of what properties they hold as part of the common good. Which makes this tale of unmitigated incompetence just that little bit more shocking.

As revealed in the Evening News today, the City of Edinburgh Council has lost the ownership of one of the handful of the most historic properties in the City. It didn’t sell it by accident in some fearful and misguided property deal. It didn’t even know that it no longer owned it. It just realised one day that something had gone very horribly wrong. Quite why remains unclear since the history of the building is very well documented in the Council’s own records.

Parliament House

The building is Parliament House which sits largely hidden from view behind the High Kirk of St. Giles and can be glimpsed from George IV Bridge just north of the National Library of Scotland. The history of the building is recounted in great detail in “The Municipal Buildings of Edinburgh – A sketch of their history for seven hundred years written mainly from the original records”, a book commissioned by the Town Council in 1895 and written by Robert Miller, the Lord Dean of Guild. The actual construction is recounted over 79 pages in “The Book of the Old Edinburgh Club”, Volume 13, 1924. This is a building about which a great deal is known.

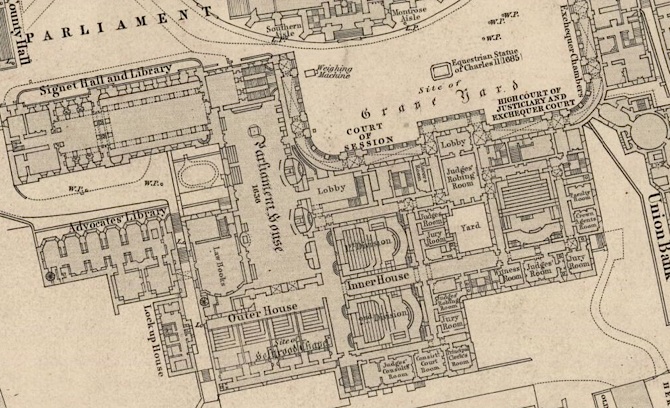

Image: Ordnance Survey 1852 Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland.

Image: Ordnance Survey 1852 Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland.

In the 16th century the Scots Parliament had no fixed abode and sat in Perth, Linlithgow, Stirling and Aberdeen as well as in Edinburgh. (2) In 1632 Charles I requested the Town Council build a new home for the Parliament and construction extended from 6 April 1632 to 11 November 1640. (Update – see comment from Alan MacDonald to effect that this is not so and that the Town Council took their own initiative. My source for this was Historical Monuments Commission). The land upon which Parliament House sits was part of the old churchyard of St Giles which was gifted to the Town Council in a Charter by Queen Mary in 1566.

The total cost of construction was £10,554,17s,7d. with 64% of the funds paid out of the common good fund and the remainder raised by public subscription from the citizens of Edinburgh. (3) The buildings were to be occupied rent free by the parliament of Scotland and the College of Justice. The Town Council paid for the upkeep of the building and for nearly two centuries Parliament House was the public hall of the city hosting civic receptions and even musical festivals. The Edinburgh Festival of 1815, 1819 and 1824 witnessed concerts of Haydn’s Creation and Handel’s Messiah.

In 1816, the Town Council handed over responsibility for the upkeep of the building to the Exchequer since the Courts of Law made almost exclusive use of it. The most recent known civic use of the building was for a reception on the occasion of the state visit of the King of Norway in 1962.

City of Edinburgh Council loses ownership

In 2004, work began on a plan to redevelop the Court of Session including Parliament House which was by now under the day-to-day administration of the Scottish Courts Service. The £60 million project was completed in 2013. In order to expedite the project, Scottish Ministers decided to record a title to the complex of buildings by way of a voluntary registration in the Land Register.

In 2005, Scottish Government solicitors appear to have been under the impression that, since the Scottish Courts Service had occupation of Parliament House, it was owned by Scottish Ministers. My understanding of what follows is derived from a source within the Scottish Government.

The Keeper of the Register of Scotland was not satisfied that Scottish Ministers had any evidence of ownership and so advised them to contact Edinburgh Council who, it was thought, was the true owner. The question was put to the Council who apparently confirmed to the Scottish Government that the it had no right, title or interest in Parliament House. The title was then registered in the name of Scottish Ministers.

Scottish Ministers’ Title – MID83631 title and plan (1.2Mb pdf)

Thus did the Council lose ownership of one of the most historic buildings in the City – a national Parliament in the capital city of an ancient European nation and a building constructed on common good land and funded by the common good fund and members of the public.

But stranger things were then to follow. The Faculty of Advocates has for centuries regarded Parliament House as theirs. They had almost exclusive use of it and so, by means as yet unclear, within a month of Scottish Ministers taking ownership, the Faculty persuaded Scottish Ministers to convey to its ownership for no consideration the room known as the Laigh Hall within Parliament House. The subjects are a bit odd comprising “the room on the lower floor shown edged red on the title plan (said subjects extending only to the inner surfaces of the walls, floor and ceiling thereof)”. The use is restricted to a library and study area for members of the Faculty of Advocates and for associated seminars and exhibitions. Scottish Ministers retain a right of pre-emption should the Faculty ever choose to sell this historic block of fresh air.

Faculty of Advocates Title – MID86039 title and plan

Why did this happen?

On what basis did the Council claim to have no interest?

The Council’s records demonstrate quite clearly that Parliament House belongs to the City.

The Council has good records of ownership

As noted by Miller in 1895, the accounts of the city 1875-76 puts on record the City’s ownership of Parliament House which had been built by the City on land owned by the City and formed part of the common good of the City. It noted that, despite the day-to-day management being in the hands of the Courts, “ownership had never been forgotten but there had not arisen any necessity to assert it.”

In the famous Report of the Common Good of the City of Edinburgh by Thomas Hunter (Town Clerk) and Robert Paton (City Chamberlain) published along with a beautiful map in 1905, it is recorded that “The large hall with certain portions around it, still belongs in property to the Corporation. The rooms underneath the large hall appear to have been handed over by the Corporation for the use of the Advocates’ Library”.

Concerned about the state of the common good in the city, in April 2006, I wrote a Report on the Common Good of the City of Edinburgh and submitted it to the scrutiny committee of the council. In it, I noted a number of properties that had been missed from the 2005 list of common good assets that had been supplied to me by the Council. These included The Meadows and Parliament House.

The Council responded in October 2006 with a Review of the Common Good in Edinburgh. It appeared to confuse Parliament House with the Old Royal High School and, uniquely among the properties being discussed, failed to address the question of Parliament House’s history. (4) I now suspect why it did this. – it was aware of the inadvertent ceding of ownership to Scottish Ministers.

What happens next?

The Council issued a terse statement to the Evening News in response to its enquiry.

“We are aware of this issue and have raised it with the Scottish Government and the Scottish Court Service.”

The owner of Parliament House is now, in law, Scottish Ministers and the Faculty of Advocates. Under the law as it was in 2006, the Council has no legal means of recovering ownership. The best that can be hoped is that Scottish Ministers and the Faculty agree to return the property to the Council’s ownership. The full council should then pass a resolution to the effect that the building is owned by the Council and forms part of the common good of the City.

This is a shocking display of incompetence by the Council. It begs the question whether anyone noticed it since 2006. Perhaps the author of the October 2006 Report did and chose to conceal the fact. The fiasco underlines the need for a proper register of common good properties and for an open and freely available land register so that the citizen can spot land transfers like this. (5)

I await developments with interest.

NOTES

Blog Updated 1045hrs 16 February after realising that October 2006 report of Council referred exclusively to Old Royal High School.

(1) Read more here and under Blog Category/Common Good

(2) See http://www.rps.ac.uk/static/mapstext.html

(3) See Accounts of the Treasurer for full details.

(4) The report then proceeds to confuse matters by claiming that it had been sold in 1977 when in fact, this refers to the Old Royal High School. See extract below.

(5) The Community Empowerment (Scotland) Bill currently before Parliament contains a provision requiring a statutory register of common good assets.

It’s scarcely credible. Are the common goods in the city not all under one particular section and probably one individual?

I appreciate the detailed history, as well as relevant to the background of the story my family were members of the former Scottish Parliament up to 1707. However going forward the court of session is a national legal institution, the parliament hall is a building of national interest and importance and I have had the privilege of seeing it personally, and I would have thought (issues of incompetence aside) that the nation (either Scottish ministers, historic Scotland or similar) should be the titular owner with any use of it being on a lease basis to the Scottish Courts Service and with public access available as often as practicable. I don’t really see what the advantage is of the council retaining ownership, perhaps you can explain?

Well I think that I should be the titular owner of your house. I really don’t see the advantage in you retaining ownership. This building belongs to the people of Edinburgh. If they wish to transfer title to Scottish Ministers, that is their perogative. But I think you would agree that they are entitled to be asked first.

Hear, hear!

Considering they haven’t used it since 1962 and Parliament Hall must cost a mint to heat and maintain, it’s a net liability so why would Edinburgh Council want it back?

If I were the Scottish Ministers and Faculty of Advocates, I would say “If the people of Edinburgh want it, they can pay to keep it up”

This is a prime example of the muddled cake and eating it thinking that surrounds common good. On the one hand people moan that CG funds performances are so poor and then the same people shriek with horror when the CG divests itself of liabilities: if you want your CG fund to be a repository of museum pieces, then you have to be prepared to pay accordingly.

Final point: What business did Queen Mary have giving a churchyard to Edinburgh TC? Is that not a “land grab”? If we’re talking about restoring PH to its rightful owners, should it not logically now be handed over to the Church of Scotland General Trustees?

Since 1816 it appears to have ben a quid pro quo. The Courts occupy it rent free in exchange for paying for the upkeep. No reason why a similar arrangement could not be entered into in a more formal way today.

Agreed.

The fact remains that the people of Edinburgh entrust their council with the management of lands and buildings held in trust for the public good. They have been doing a very poor job of it, and many deserve to be sacked.

There needs to be more transparency, and public involvement in decisions that affect buildings held and managed for the public.

As for Neil King’s comments, the City of Edinburgh derives a considerable sum from the visiting tourists from all corners of the globe who come to see this magnificent, historic city.

These historic buildings are the legacy of the people of Edinburgh, and as such, should be protected, maintained, and put to good use. These buildings were made to last centuries, unlike the new prefabricated sandstone and glass, or concrete monstrosities that need repair within years. Look at the modern Scottish Parliament building! It’s a disgrace that it cost so much when there are perfectly suited older buildings that could have been made useful for a fraction of the cost.

The Church of Scotland did not fall heir automatically to the property of the Catholic Church at the Reformation. Under feudal principles it reverted to the crown.

As far as ownership of the building is concerned, surely the point is that, since it was the property of Edinburgh Council, it was theirs to sell or dispose of to the benefit of the city, and yet they disowned it, apparently believing that it didn’t belong to them. They could surely have leased it to the courts service for goodness sake!

Thanks Alan – have made note in the text. My source was entry in Historical Monuments Commission.

I’m in no way an expert beyond reading the facts stated in this article, but from what I read here the Scottish Courts Service have enjoyed lease-free use of the building since the 18th Century. They of course were paying for the upkeep. By registering the building Scottish Ministers & co. managed to secure ownership of the building that belonged to the people of Edinburgh for absolutely no cost. I’d love to see an estimate of the cost of the building, especially considering its location.

It may now belong to Scottish Ministers and friends by law, but they really should cede ownership back to CEC. And if SM et al really want the building, they can purchase it, or some kind of lease agreement can be reached that is above-board and with both parties knowing who the building really belongs to.

Luke, that line of argument only works if the property could ever realistically be sold. Imagine the howls of protest if CEC were to say “Right, now we’ve got PH back, we’re going to flog it off for £X bazillion to Donald Trump …”.

i’m staggered that Edinburgh council could be so negligent. I did some work on the subject myself a few years back, published as ch. 6 of my book ‘The Burghs and Parliament in Scotland 1550-1651’. Not only was it paid for by he council and continued to belong to them, it was NOT ordered to be built by Charles I (a myth for which there is not a shred of evidence in contemporary sources), rather he council chose to do it off its own bat.

So the building has been used rent free since 1962 ! by the Scottish Ministers and Faculty of Advocates, well if the verbal agreement of costs and upkeep by the societies mentioned against use was to change, then we should consulted. The people of Edinburgh should ask these bodies for a fair rent, and pay the up keep. Incidentally, who has paid for the upkeep since 1962? If the property was a burden to the the local council and seen not to be covering its costs it could be sold. It is a prime piece of real-estate in the centre of Edinburgh.

Well done Andrew. Another startling story – heritage disposed off by sleepwalkers

The Faculty of Advocates tried to close Parliament House to the public in the 1830’s and there was such an outcry from the public and the Council that they retreated. I read this in one of the local newspapers (not apparently the Scotsman as I cannot find it there in a search).

The Royal Charter of Queen Mary included a much larger area that extended right across to where the original High School stood and the first College of Surgeons. James VI ratified Mary’s Charter in 1582, reinforcing her desire that the area should be used for educational purposes. The University of Edinburgh was then built on the land.

“The Faculty of Advocates tried to close Parliament House to the public in the 1830s”. This is nonsense.

Andy, as a matter of interest, what was your response to the October 2006 Report by CEC at the time? I presume you would have mentioned if you’d challenged them at that time on the fact they’d appeared to have omitted PH by confusing with the Royal High. Did you just not notice?

I questioned their assertion in a follow-up paper in which I noted that they had confused the two properties. There was a further paper which perpetuated the confusion as far as I recall. I was in Ethiopia at the time and it was very difficult to follow the progress. At the time, of course I knew nothing of Parliament Hall. I now realise why I think they refused to address the question of Parliament Hall.

Given the record of Edinburgh Council’s competence or lack thereof it may be better that this building is held and administered by Scottish Ministers on behalf of the people of Edinburgh (and the Nation.)

I have noticed with some alarm the cavalier attitude of many Councillors in my own area to ‘common good’ matters so it may be time to change who has stewardship of these assets.

Here are a few links, indicative of CEC’s record keeing and accounting in relation to Common Good assets since 2005:

1997 – 2004 – Extracts of Common Good Accounts from the Annual Accounts of the City of Edinburgh Council

http://www.scottishcommons.org/las/cityofedinburgh.htm

February 2005 – Annual Report on the City’s Common Good Fund:

http://www.edinburgh.gov.uk/download/meetings/id/18194/annual_report_on_the_citys_common_good_fund

January 2014 – Management of Common Good Assets

http://www.edinburgh.gov.uk/download/meetings/id/41930/item_719_-_management_of_common_good_assets

July 2014 – Common Good Annual Performance 2013/14

http://www.edinburgh.gov.uk/download/meetings/id/44003/item_76_-_common_good_annual_performance_2013-14

They don’t seem to raise much cash given the value of property they hold. Dumbarton Common Good Fund donates around £100k- 200k/yr to local groups from surplus income.

Wul, that might be because the Edinburgh CG account is dominated by assets (like the Meadows etc.) which are very valuable “on paper” but in practice can never be realised because of the political stink if the Council ever attempted to sell “the family silver”: Andy himself was at the forefront of objections to selling Waverley Market for e.g. Also, these “assets” yield no income but suck up masses in terms of maintenance and repair etc.

Dumbarton might be more fortunate that the assets on its CG account are generally less controversial things like stocks and shares which can be traded with impunity and yield a reasonable income which can be distributed to good causes etc.

It’s accidents of history. People talk about historic mismanagement of CG funds but it’s possible (I’m not saying this is true) that Dumbarton was shrewder by flogging off its family silver back in an era when these things weren’t questioned so much. Look who’s having the last laugh now!

I am astonished that the Faculty of Advocates both made such a modest claim to the property and that none of their members bothered to check who held title to one of their most significant places of work and challenge its nationalisation contrary to the interests of the citizens of Edinburgh when so many of its members are the same. Neither finest hour of the Faculty nor an advertisement for the diligence which its members are assumed to maintain. At the very least I would have expected a case before the Outer House argued by an advocate representing the Freemen of St Giles. Amazing how something so close to home escaped their collective notice.

testing

Visitors to Edinburgh find themselves in Parliament Square, but there is no indication whatever of where Parliament House can be found. I would actually very much like to be able to visit, instead of having to show people a photograph of a distant glimpse of part of the building taken from George 1V Bridge. So whoever owns it, pays for its upkeep, folk should be able to see and enjoy such a historic building.

It’s open to the public, effectively during office hours during the week (also on Doors Open Day). Go in the door at the south-west corner of Parliament Square. Booklets on the buildings and their history are for sale in the lobby.

Ok if the building is now in the hands of Scottish ministers, I wonder what the implications are?

Is it still effectively held in trust or can they sell it, knock it down or house the homeless in it?

Inclined to agree about the faculty of advocates not seeming too bothered.

Is there a graveyard under parliament square?

I don’t think if I may say so that this makes a proper distinction between that part of Parliament House that was built in the C17 and the modern complex as a whole, shown by your plans, which is far larger. Taking your useful 1852 map, the Parliament House as built and owned by the City consisted only of Parliament Hall, the lobby, and a fairly small area (now the public benches at the back of Court 1) running from the ‘E’ in ‘Session’ in the Graveyard south to the ‘r’ in ‘Inner’, with the corridor in between, and of course the land below. The history of the rest of the modern complex is quite different. There’s a lot of material as to this in the planning applications made by Scottish Ministers (to CEC of course) for the C21 redevelopment and the associated papers which would repay study.

On the Laigh Hall, after Cromwell’s cavalry (who used it as stables) had left, this was effectively in the exclusive possession of the Faculty of Advocates- at least since the early eighteenth century- and used until the last century as library storage. But this was (with some small possible exceptions) the only part of the complex that could be said to be in the Faculty’s possession, and I dare say the reason it only claimed this was that this was the only part that it had always claimed. The statement ‘The Faculty of Advocates has for centuries regarded Parliament House as theirs. They had almost exclusive use of it…’ is simply not true; it may reflect a confusion between the Faculty of Advocates and the College of Justice (i.e. the Supreme Courts).